Educators Tour North Canadian River Watershed

Through rivers, around buttes, and over dunes, the North Canadian River Watershed Traveling Educator Workshop combines 24 educators, three days, and one bus for an action packed crash course on watershed ecology, geology, and responsible natural resource management. After participating in this X-Games of educator workshops on June 10-12, 2014, participants returned to classrooms, labs, and community centers equipped with the skills and tools necessary to effectively incorporate watershed stewardship into their instruction.

What is a watershed?

A watershed is an area of land wherein all of the water above and below it drains to the same place—in many cases, a river. As seen in the above map, the North Canadian River watershed begins at the confluence of Beaver River and Wolf Creek and ends when it joins the Canadian River at Lake Eufaula. The North Canadian flows through a valley cut into a narrow ridge of elevated terrain and is bounded by the Cimarron and Canadian River watersheds to the north and south of that elevation respectively.

Beaver River

Beginning in El Reno, the tour bus travelled 200 miles west to the dry bottom of the Beaver River in the easternmost county of the Oklahoma panhandle. Despite draining most of the panhandle, these headwaters of the North Canadian are often dry due to minimal rainfall. The situation is exacerbated by salt cedar infestation.

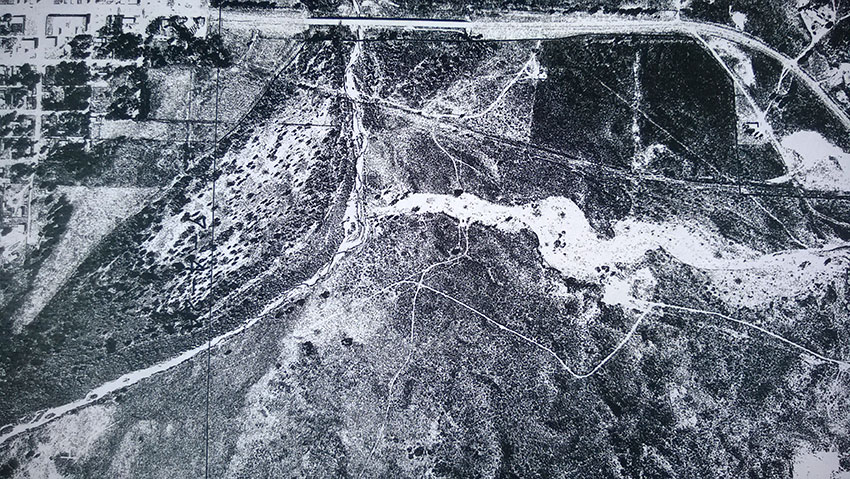

This invasive plant from the arid Mediterranean coasts of Africa and Eurasia was originally imported to North America to decorate lawns. The plant quickly escaped its domestic confines and spread throughout the American West. Salt cedars consume large amounts of groundwater due to the density of their stands relative to those of native species and make the formation of standing water even more difficult in dry regions. Thick salt cedar stands can be seen in the background of the above photo taken on the first stop of the tour. Below, aerial views from 1985 and 2012 respectively show the spread of salt cedar near the tour stop. Notice how water in the river vanishes as the trees expand their territory.

Beaver Dunes

At Beaver Dunes the tour stopped to continue progress towards Project WET certification—did we mention all participants learn enough activities to earn Project WET instructor certification? In the activity pictured above called 8-4-1, each person of the eight person team represents a different sector of water users, such as energy or municipal. Prior to beginning the activity, each sector must brainstorm and share with the group ways their sector uses water. In the activity, the team must use strings tied to a rubber band to move a can of water from one location to another without spilling. The activity demonstrates the interconnected needs of water users and how we must work together in order to ensure everyone’s needs are met.

With the water can safely transported, the team climbed the nearby Beaver Dunes. Retired USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) state soil scientist, Greg Scott, explained how the dunes were formed. During dry periods, sand from the Beaver River to the south blows from the river bottom and collects in Beaver Dunes Park. Over millennia, the dunes grow to immense sizes and even move slowly over the plains. A parker ranger described how noticeably different the dunes were positioned only of decade ago.

Life Beneath an Overpass

A noisy concrete overpass is hardly where you’d expect to find an abundance of wildlife, but that’s exactly what happened when the tour stopped where the Beaver River flows near Laverne in Harper County. Above, hundreds of cliff swallows hunt for grass hoppers as the group hikes to the river. The resourceful birds live in mud nests caked to the underside of the bridge.

After some diligent fishing, the group turned up several minnows, tadpoles, and even a crayfish. Unfortunately, more sensitive creatures such as a stoneflies and hellgrammites (types of aquatic insect larvae) were nowhere to be found. Though no chemical testing was done on the water, the lack of these species is a good indicator that this stretch of stream’s health is suffering.

We also found snake skin and a six-lined racerunner lizard.

Before turning in for the day, Dust Bowl historian and survivor, Pauline Hodges, described life during those harsh times. She encouraged educators to take the lessons of the past into their classrooms to ensure we do not repeat the same land abuses and overuses committed in the 1920s-30s. During that period, constant plowing and overgrazing allowed wind and water to erode vast tracts of prairie, crippling Great Plains agriculture and intermittently blackening the sky with dust for over a decade.

The evening wrapped up with an enlightening visit to the Plains Indian and Pioneer Museum in Woodward. Using authentic artifacts and three-dimensional maps, a tour guide illustrated the cultural and ecological changes that have occurred within the North Canadian watershed since the arrival of European settlers. It allowed participants to make connections between the landscape they studied all day and the culture that, for better or worse, played a large hand in shaping it. Unfortunately, three Oklahoma Conservation Commission (OCC) staff had to be “locked-up” in the museum’s replica jail due to “an overabundance of joviality.”

Cool Waters at Boiling Springs

Day two began at Boiling Springs State Park east of Woodward with another Project Wet activity—Thirsty Plants. In this activity, plastic bags are fastened around the leaves of various plants in the same area for 24 hours. When the bags are collected, participants can see how much water has transpired from the plants. Karla Beatty, OCC education coordinator, explained why some plants transpire more than others and how that affects ecosystems. As you can see in the above photo, a wetlands plant such as the willow transpires quite a lot over 24 hours. Of course, in a wetlands environment, there’s plenty of water to go around. Slightly off camera to the left is a salt cedar sample which has transpired nearly as much as the willow. This is a problem because the cedar can survive in areas with far less available water but continue to transpire just as much.

After seeing a relatively unhealthy stream the day before, educators got to study a much healthier one at Boiling Springs. Being in a state park, the stream is less likely to receive harmful runoff from human activity, and the well-vegetated banks are more resistant to erosion. The stream itself, with its sandy bottom, grasses, tall reeds, and good shade provided by trees is able to provide much better and diverse habitat for aquatic wildlife.

While identifying trees, someone spotted this porcupette (young porcupine) taking refuge in a tree. The two orange lumps near its eye are ticks engorged with blood.

As participants dried off from their dip in the creek, OCC’s Water Quality Division educational outreach branch, Blue Thumb, used the ground water model to demonstrate how water behaves beneath our feet. Candice Miller, Blue Thumb education coordinator, pointed out that contrary to popular ideas, most ground water does not exist in vast underground caverns, but in the tiny spaces between sand and gravel. Given this fact, the model pictured above is a decent replica of subterranean water behavior. For example, let’s say the red dye represents a leaking sewage pipe. Despite the great distance between them, the sewage will eventually seep into the well where Candice is pumping on the other side of the model.

Lake Canton Dam Talk

The North Canadian is dammed at Canton Lake in Blaine and Dewey Counties to provide flood protection and municipal water to Oklahoma City. From the Canton Dam overlook, Johnny Pelley, OCC watershed technician, demonstrated how a flood control dam functions using a stream bank trailer constructed by OSU Extension. OCC and conservation districts operate and maintain 2,107 flood control dams across the state. Canton Dam is maintained by the US Army Corps of Engineers.

The tour paused for a quick photo from the Canton Dam overlook. It was very windy.

The Unbreakable Bond of Land and Water

As the tour made its meandering return to El Reno on the third day, educators got a firsthand experience with modern agricultural conservation techniques in action. They first visited a farm which had recently converted to no-till farming—that practice of leaving soil covered in plant residue and not turning soil over before planting. Using clods of tilled and no-till soil, Greg Scott demonstrated why conservation isn’t just good for our environment, but for farmer’s pocket books. When soil isn’t tilled, worms and roots form channels that allow it to naturally take in more water, and undisturbed fungus in the soil acts as a sponge to lock in moisture and nutrients. Furthermore, residue on the soils surface left behind from a previous harvest shades soil from the scorching sun and protects it from wind and water erosion.

Above, we see tilled soil dissolving in water on the left while no-till soil holds firm and healthy on the right.

The group examined cores of soil extracted from a field which had been tilled for so long, the farmer had converted it to livestock grazing because the soil health was too poor to support food crops. Despite rain that very morning, the soil samples had very little moisture even near the surface and were nearly as hard as bricks near the bottom. It will take years of not being tilled for soil in such poor condition to recover the necessary organic matter to support crops again.

A little farther down the road, the tour took a hay ride through a cattle ranch which participated in OCC’s riparian exclusion program. A riparian zone is the land within several hundred feet of a stream or river. By excluding this area from agricultural production and allowing native vegetation to thrive there, riparian zones form a buffer against runoff for rivers as well as an excellent food source for responsibly managed grazing livestock.

Thanks to riparian exclusion, the North Canadian riverbank pictured above has a variety of native plants keeping the soil in place and providing food and habitat to native wildlife.

The tour concluded with minds full of teaching ideas and bags full of materials on the shores of Lake Overholser. OCC would like to thank all of the public school, tribal, and government educators for your attendance and assistance in making the 2014 educator tour a productive and memorable experience.